Human Orbital Spaceflights

![]()

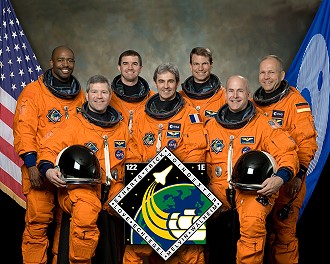

International Flight No. 254STS-122Atlantis (29)121st Space Shuttle missionUSA |

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

Launch, orbit and landing data

walkout photo |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

alternative crew photo |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

alternative crew photo |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Crew

| No. | Surname | Given names | Position | Flight No. | Duration | Orbits | |

| 1 | Frick | Stephen Nathaniel | CDR | 2 | 12d 18h 21m 38s | 202 | |

| 2 | Poindexter | Alan Goodwin "Dex" | PLT, IV-1 | 1 | 12d 18h 21m 38s | 202 | |

| 3 | Melvin | Leland Devon "Lee" | MS-1, SSRMS, RMS | 1 | 12d 18h 21m 38s | 202 | |

| 4 | Walheim | Rex Joseph | MS-2, EV-1, FE | 2 | 12d 18h 21m 38s | 202 | |

| 5 | Schlegel | Hans Wilhelm | MS-3, EV-2 | 2 | 12d 18h 21m 38s | 202 | |

| 6 | Love | Stanley Glen | MS-4, EV-3, SSRMS | 1 | 12d 18h 21m 38s | 202 | |

| 7 | Eyharts | Léopold Paul Pierre | MS-5 | 2 | 48d 04h 53m 36s | 758 |

Crew seating arrangement

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Backup Crew

|

|

||||||||||

Hardware

| Orbiter : | OV-104 (29.) |

| SSME (1 / 2 / 3): | 2059-2 (2.) / 2052-2 (6.) / 2057-2 (3.) |

| SRB: | BI-132 / RSRM 99 |

| ET: | ET-125 (SLWT-29) |

| OMS Pod: | Left Pod 04 (29.) / Right Pod 01 (36.) |

| FWD RCS Pod: | FRC 4 (29.) |

| RMS: | 301 (26.) |

| EMU: | EMU No. 3017 (PLSS No. 1017) / EMU No. 3015 (PLSS No. 1015) |

Flight

|

Launch from Cape Canaveral (KSC) and

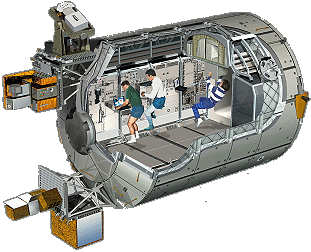

landing on Cape Canaveral (KSC), Runway 15. The original target launch date for STS-122 was December 06, 2007, but due to engine cutoff sensor (ECO) reading errors, the launch was postponed to December 09, 2007. During the second launch attempt, the sensors failed again, and the launch was halted. A tanking test on December 18, 2007 revealed the probable cause to lie with a connector between the external tank and the shuttle. The connector was replaced and the shuttle launched during the third attempt on February 07, 2008. The primary objective of STS-122 (ISS 1 E Columbus) was to deliver the European Columbus science laboratory, built by the European Space Agency (ESA), to the station. STS-122 also carried the Solar Monitoring Observatory (SOLAR), the European Technology Exposure Facility (EuTEF), and a new Nitrogen Tank Assembly, mounted in the cargo bay of an ICC-Lite payload rack, as well as a spare Drive Lock Assembly (DLA) sent to orbit in support of possible repairs to the starboard Solar Alpha Rotary Joint (SARJ) which is malfunctioning. Several items were returned with Atlantis: A malfunctioning Control Moment Gyroscope (CMG) that was swapped out with a new one during STS-118, and the empty Nitrogen Tank Assembly will be placed in the orbiter's payload bay, along with a trundle bearing from the Starboard SARJ that was removed during an EVA performed by Expedition 16. Expedition 16 Flight Engineer Daniel Tani, who traveled to the space station on the STS-120 mission, returned home with the STS-122 crew. Léopold Eyharts joined the Expedition 16 crew, serving with Commander Peggy Whitson and Flight Engineer Yuri Malenchenko. The Columbus laboratory is the cornerstone of the European Space Agency's contribution to the International Space Station (ISS) and is the first European laboratory dedicated to long-term research in space. Named after the famous explorer from Genoa, the Columbus laboratory will give an enormous boost to current European experiment facilities in weightlessness and to the research capabilities of the ISS once it becomes an integral part of the space station. The 7-meter-long (23-foot-long) Columbus laboratory consists of a pressurized cylindrical hull 4.5 meters (14.7 feet) in diameter, closed with welded end cones. To reduce costs and maintain high reliability, the laboratory shares its basic structure and life-support systems with the European-built multi-purpose logistics modules (MPLMs): pressurized cargo containers, which travel in the space shuttle's cargo bay. The primary and internal secondary structures of Columbus are constructed from aluminum alloys. These layers are covered with a multi-layer insulation blanket for thermal stability and a further two tons of paneling constructed of an aluminium alloy together with a layer of Kevlar and Nextel to act as protection from space debris. The Columbus Laboratory has a mass of 10.3 tons and an internal volume of 75 cubic meters (98 cubic yards), which can accommodate 16 racks arranged around the circumference of the cylindrical section in four sets of four racks. These racks have standard dimensions with standard interfaces, used in all non-Russian modules, and can hold for example experimental facilities or subsystems. Ten of the 16 are International Standard Payload Racks fully outfitted with resources (such as power, cooling, video and data lines), to be able to accommodate an experiment facility with a mass of up to 700 kilograms (1,543 pounds). This extensive experiment capability of the Columbus laboratory has been achieved through a careful and strict optimization of the system configuration, making use of the end cones for housing subsystem equipment. The central area of the starboard cone carries system equipment such as video monitors and cameras, switching panels, audio terminals and fire extinguishers. Although it is the station's smallest laboratory module, the Columbus laboratory offers the same payload volume, power, and data retrieval, for example, as the station's other laboratories. A significant benefit of this cost-saving design is that Columbus will be launched already outfitted with 2,500 kilograms (5,511 pounds) of experiment facilities and additional hardware. The crew of Atlantis spent the second flight day performing a variety of tasks designed to prepare the shuttle for docking on Saturday, including the installation of the centerline camera, and the extension of the orbiter docking system ring. A majority of the day's activities was devoted to inspecting the shuttle's thermal protection system using the Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS). Early in the morning, the crew performed a burn of the Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines to adjust the orbit in preparation for docking with the International Space Station. About 2.5 hours before docking, Atlantis' jets were fired during what is called the Terminal Initiation burn to begin the final phase of the rendezvous. Atlantis closed the final miles to the station during the next orbit. As Atlantis moved closer to the station, the shuttle's rendezvous radar system and trajectory control sensor tracked the complex and provided range and closing rate data to the crew. During the final approach, Atlantis executed several small mid-course correction burns that placed the shuttle about 1,000 feet (304.8 meters) directly below the station. STS-122 Commander Stephen Frick then manually controlled the shuttle for the remainder of the approach and docking. Stephen Frick stopped the approach 600 feet (182.9 meters) beneath the station to ensure proper lighting for imagery prior to initiating the standard Rendezvous Pitch Maneuver (RPM), or R-bar Pitch Maneuver (RPM), or backflip. Stephen Frick maneuvered Atlantis through a 9-minute, 360-degree backflip that allowed the station crew to take as many as 300 digital pictures of the shuttle's heat shield. On verbal cue from Pilot Alan Poindexter to the station crew, Stephen Frick commanded Atlantis to begin a nose-forward, three-quarter of a degree per second rotational backflip. Both 400- and 800-mm digital camera lenses were used to photograph Atlantis by station crew members. The 400 mm lens provided up to 3-inch (7.6 centimeters) resolution and the 800 mm lens could provide up to 1-inch (2.5 centimeters) resolution. The imagery included the upper surfaces of the shuttle as well as Atlantis' underside, capturing pictures of the nose landing gear door seals, the main landing gear door seals and the elevon cove. The photos were taken out of windows in the Zvezda Service Module using Kodak DCS 760 digital cameras. The imagery was one of several inspection techniques to determine the health of the shuttle's thermal protection system, including the tiles and reinforced carbon-carbon wing leading edges and nose cap. The photos were downlinked through the station's Ku-band communications system for analysis by systems engineers and mission managers. When Atlantis completed its rotation, its payload bay was facing the station. Stephen Frick then moved Atlantis to a position about 400 feet (121.9 meters) directly in front of the station in preparation for the final approach to docking to the PMA-2, newly located at the end of the Harmony module. The shuttle's crew members operate laptop computers processing the navigational data, the laser range systems and Atlantis' docking mechanism. Using a view from a camera mounted in the center of the Orbiter Docking System, Stephen Frick precisely matched up the docking ports of the two spacecraft. He paused 30 feet (9.14 meters) from the station to ensure proper alignment of the docking mechanisms. For Atlantis' docking on February 09, 2008, Stephen Frick maintained the shuttle's speed relative to the station at about one-tenth of a foot per second (3 centimeters per second) (while both Atlantis and the station were traveling at about 17,500 mph = 28,163 km/h), and kept the docking mechanisms aligned to within a tolerance of three inches (7.6 centimeters). When Atlantis made contact with the station, preliminary latches automatically attached the two spacecraft. Immediately after Atlantis docked, the shuttle's steering jets were deactivated to reduce the forces acting at the docking interface. Shock absorber springs in the docking mechanism dampened any relative motion between the shuttle and the station. Once the motion between the spacecraft had stopped, the docking ring was retracted to close a final set of latches between the two vehicles. After working through a variety of leak check procedures, the hatches were opened between the shuttle and station at 18:40 UTC, and the two crews exchanged greetings and conducted a mandatory safety briefing. After the briefing, they began the rest of the day's tasks, including moving the station's robotic arm to grapple the OBSS, and then hand it off to the shuttle's robotic arm in preparation for future activities. The official exchange of Expedition 16 crewmembers Daniel Tani and Léopold Eyharts was completed in the evening, when they exchanged their Soyuz custom made seat liners, and Daniel Tani became a member of the STS-122 crew, while Léopold Eyharts began his position as Flight Engineer for Expedition 16. The two crews spent their first joint mission day working through a focused inspection of the OMS pod blanket, reviewing the upcoming EVA procedures, and beginning the transfer of items from the shuttle to the station. Earlier in the day, ESA confirmed the crewmember with the medical condition was Hans Schlegel, but stated it was nothing serious and does not impact the health of any of the other crewmembers. Managers had decided to make a 24-hour delay to EVA-1, originally scheduled for Flight Day 4, and that Stanley Love would replace Hans Schlegel for EVA-1. The first EVA by Rex Walheim and Stanley Love occurred on February 11, 2008 (7h 58m) was delayed 24 hours. They prepared the Columbus module for installation on Harmony. Originally it was planned that Rex Walheim and Hans Schlegel had to do this EVA, but Hans Schlegel became ill (probably he suffered on the space adaption syndrome), so Stanley Love had to do the first EVA. They installed the Power Data Grapple Fixture on Columbus, which allowed the space station’s robotic arm to grab the module and move it from the shuttle’s payload bay to Harmony at the end of this spacewalk. Preparing work to remove the Nitrogen Tank Assembly, a part of the station’s thermal control system, from the P1 truss was the next task. The tasks took more time than planned. At time they were one full hour behind the timeline. The main task was to prepare the Columbus module for installation on Harmony. They installed the Power Data Grapple Fixture on Columbus, which will allow the space station's robotic arm to grab the module and move it from the shuttle's payload bay to Harmony. The spacewalkers also began work to remove the Nitrogen Tank Assembly, a part of the station's thermal control system, from the P1 truss. The assembly needs to be replaced because the nitrogen is running low. Rex Walheim and Stanley Love completed the preparations for the unberthing of Columbus from the payload bay, and with Leland Melvin inside the space station working the robotic arm, the module was successfully lifted out of the payload bay. Rex Walheim and Stanley Love completed the preparations for the unberthing of Columbus from the payload bay, and with Leland Melvin inside the space station working the robotic arm, the module was successfully lifted out of the payload bay. The first contact of Columbus with the station was at 21:29, and at 21:44, Léopold Eyharts announced that Columbus was officially installed on its new home in orbit. The two crews spent the flight day 6 working to activate and outfit the newest addition to the station, the Columbus module. After the ground conducted a variety of leak checks during the crew's sleep period the night before, the crew was given the go ahead to put the module into what is called "Berth Survival Mode", which is a "functional mode": A minimal healthy configuration that can be maintained for extended time periods, if required. This involved powering up basic computers, power distribution units, and heaters. The crew completed the Berth Survival Mode activation quickly, and moved on to final activation. Representing the European partners, Hans Schlegel and Léopold Eyharts were the first crewmembers to enter the module, performing a partial ingress at 14:08 UTC Léopold Eyharts told the team on the ground, "We have a special thought at this moment for all the people in Europe and the U.S. who have contributed to the make-up of Columbus. Especially to the space agencies, of course, the industry, but also all the citizens who are supporting space flight. This is a great moment, and Hans and I are very proud to be here and to ingress for the first time the Columbus module." The second EVA was performed by Rex Walheim and Hans Schlegel on February 13, 2008 (6h 45m) to remove the old NTA and temporarily store it on an equipment cart. They then installed the new one. The old NTA was transferred to the shuttle's payload bay for return home. The third and final EVA by Rex Walheim and Stanley Love was conducted on February 15, 2008 (7h 25m) to install two payloads on Columbus' exterior: SOLAR, an observatory to monitor the sun; and the European Technology Exposure Facility (EuTEF) that will carry eight different experiments requiring exposure to the space environment. Move of a failed control moment gyroscope from its storage location on the station to the shuttle's payload bay for return to Earth. At undocking time, the hooks and latches were opened, and springs pushed the shuttle away from the station. Atlantis' steering jets were shut off to avoid any inadvertent firings during the initial separation. Once Atlantis was about two feet (61 centimeters) from the station and the docking devices were clear of one another, Alan Poindexter turned the steering jets back on and manually controlled Atlantis within a tight corridor as the shuttle separated from the station. Atlantis moved to a distance of about 450 feet (137.2 meters), where Alan Poindexter began to fly around the station in its new configuration. Once Atlantis completes 1.5 revolutions of the complex, Alan Poindexter fired Atlantis' jets to leave the area. The shuttle moved about 46 miles (74 km) from the station and remained there while ground teams analyzed data from the late inspection of the shuttle's heat shield. The distance was close enough to allow the shuttle to return to the station in the unlikely event that the heat shield is damaged, preventing the shuttle's re-entry. |

EVA data

| Name | Start | End | Duration | Mission | Airlock | Suit | |

| EVA | Walheim, Rex | 11.02.2008, 14:13 UTC | 11.02.2008, 22:11 UTC | 7h 58m | STS-122 | ISS - Quest | EMU No. 3017 |

| EVA | Love, Stanley | 11.02.2008, 14:13 UTC | 11.02.2008, 22:11 UTC | 7h 58m | STS-122 | ISS - Quest | EMU No. 3018 |

| EVA | Walheim, Rex | 13.02.2008, 14:27 UTC | 13.02.2008, 21:12 UTC | 6h 45m | STS-122 | ISS - Quest | EMU No. 3017 |

| EVA | Schlegel, Hans | 13.02.2008, 14:27 UTC | 13.02.2008, 21:12 UTC | 6h 45m | STS-122 | ISS - Quest | EMU No. 3015 |

| EVA | Walheim, Rex | 15.02.2008, 13:07 UTC | 15.02.2008, 20:32 UTC | 7h 25m | STS-122 | ISS - Quest | EMU No. 3017 |

| EVA | Love, Stanley | 15.02.2008, 13:07 UTC | 15.02.2008, 20:32 UTC | 7h 25m | STS-122 | ISS - Quest | EMU No. 3018 |

Note

Photos / Graphics

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

more EVA photos |

|

| © |  |

Last update on March 27, 2020.  |

|